The End of the World Used to Seem So Cool

The end of the world used to seem so cool. I’d get to go days without shaving, acquire a cool long coat, and sleep on a cot next to pallets of canned soup and a loaded shotgun. Plus, everyone would dress like the Legion of Doom. What’s not to love?

Then I had kids.

All of the sudden, the bloom was off the rose of people dying horrifically. I remember watching a Final Destination movie, absolutely appalled. At myself and at all the thousands of moviemakers who all decided Rube Goldberg snuff films were a fun way to spend a Saturday afternoon. (Also appalled by the characters: honestly, if God is setting deathtraps for you, maybe put off buying a nail gun at Home Depot.)

Facing your own death is one of the universal things each person has to do. Spoiler alert: I’m going to die, you’re going to die, everyone not named MacLeod will die. But we usually get to do it in our own time, whatever that may be. Every second we’re alive is another second to either wonder at it, or to tremble and quake that it will one day end.

But the end of the world makes us have to come to grips with a whole lot more death than just our own. Sheep in a meadow, that Zinnia bush, the actress who played Becky on Roseanne, the other actress who played Becky on Roseanne: each one needs its own mourning period. And it’s not like they’re staggered: it all slams up at the same time. Your grief circuitry will feel like the Cross-Bronx Expressway ten minutes after a Yankees game is over.

I have a way to avoid all of this: the solution is to use magical thinking to believe I’ll survive. That way, I only have to think about the rest of creation biting it, not me. You can do it, too! All you need is the ability to cross your fingers and say “la la la” over and over.

The individual, single-serving size of death is fine to grapple with, because it’s the price of life, and that lets you think about all the rest of life: the romance and betrayals, the raptures and torments, and (as Warren Zevon said) the sandwiches. I’ll die, but I’ll have done my best to help leave the world a little better than I came into it.

The apocalypse treats all of those nice comforting thoughts like a foot in a sand castle. Everyone’s going to die, and quickly, but not so quickly we won’t be terrified and live our final days in despair and indignity. Whatever you don’t want out of life can be found in what’s approaching us in an elliptical orbit. There is no silver lining. There is no Cracker-Jack prize. We’re veal that no one will eat.

There’s another story about all the evils of the world being released upon it. It involves a curious woman named Pandora, and a toilet. (Bowdlerized retellings will upgrade this to a box.) She wants to see what’s inside–which, knowing that it was originally a toilet, ew. And she opens the lid, and all life’s troubles spill out. But the box also contained a secret weapon, armor and spear and castle and elixir all in one.

The secret weapon found in the bottom of the box was hope.

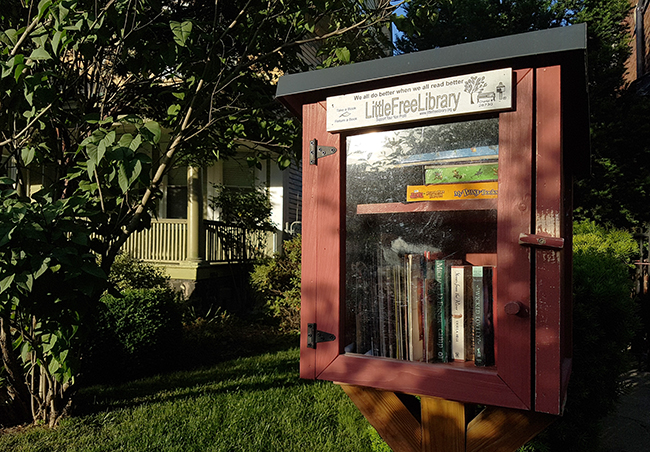

Hope would be the engine behind a million wishes of the million survivors: that we could collect enough food in the days before to see our families through. That we’d be spared the immediate impact. That we’d never have to trade our lives for another’s. That we’d be able to drink the water again one day, and that the ground would still yield crops. That we could treat this like a do-over, reverting back three thousand years on our global saved file.

Hope would make me think we could all survive, and by “survive” I mean both mentally and physically. What we take for granted now – a safe warm bed, four walls no one’s dying outside of, full bellies, things to do tomorrow other than try not to die – that would be what we’d aspire to. We’d want our kids to have a better life. And we’d want to stick around to see grandchildren.

These hopes, it turns out, are the hopes that everyone has, not just those of us under the cosmic barrel of a celestial cannon. They’re universal, even when the universe is playing pool and we’re the eight-ball.

Maybe one day, after it’s over, we can even be nostalgic for the days when the skies grew dark and no one knew when a cloaked visitor with a scythe would show up, chessboard in hand.

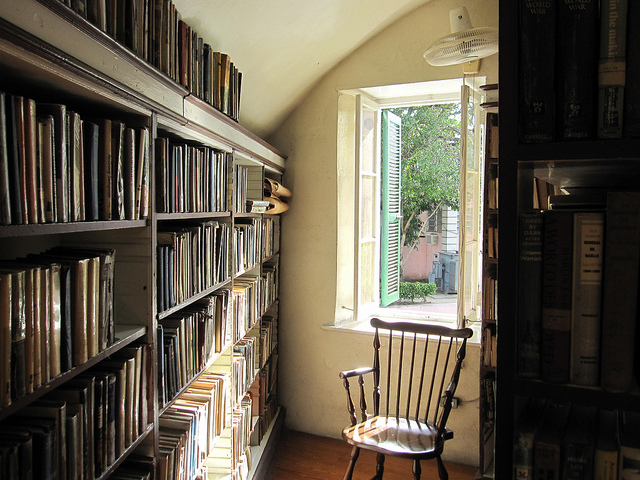

“You young kids, with your potable water and your not coughing to death! In MY day, life was tough! You’d never see me reading a book! Playing a video game! It made up feel alive! Some days I really miss befouling myself in fear.”

Jeff Ryan is the author of Super Mario: How Nintendo Conquered America. He hopes the can of guava paste in the back of the pantry counts as a disaster preparedness kit.