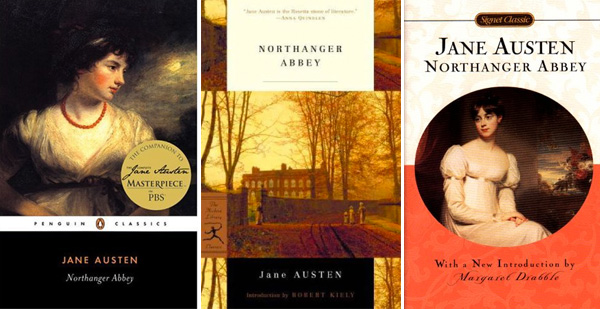

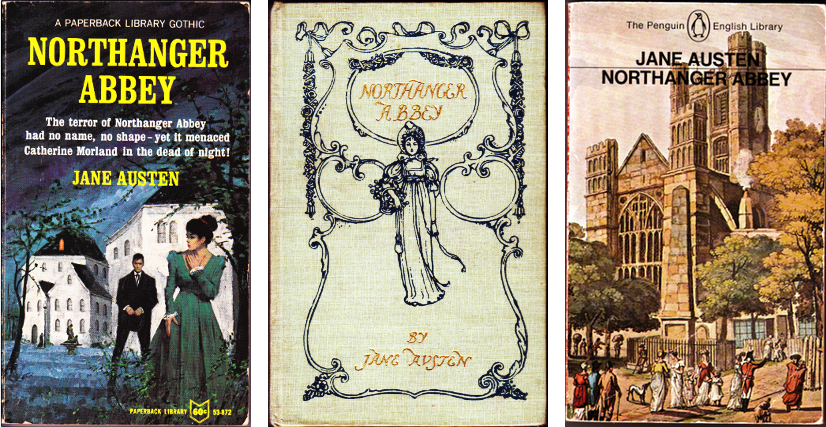

In Training For a Heroine: The Great Northanger Abbey Re-read, Part I

It’s officially Austen Month here at Quirk (Jane Austen Cover to Cover is almost out!), and what better way to celebrate than to revisit one of the great authoress’s beautiful novels. All month long, I’ll be reading and recapping Northanger Abbey, Austen’s love letter cum parody of the gothic novels of her day. I plan on going chapter by chapter for the next few weeks, and please consider this your cordial invitation to join in, whether that means reading along, or just commenting!

First off, my credentials: I first picked up Pride and Prejudice when I was 13 years old after being told that it was a “difficult book” and I would “probably have trouble with it.” I blew through it, fell very much in love with Austen’s sardonic style, and felt extremely pleased with myself for having proven the naysayers wrong. (Has trying to discourage a bookworm from reading ever actually worked? I’m genuinely curious.) In the following decade I read Austen’s other novels, determined that Persuasion was probably my favourite, watched pretty much every movie adaptation available, and was informed that I most closely resemble Sense and Sensibility’s Elinor Dashwood by a Which Austen Heroine are You quiz. So yeah, pretty much an expert.

Let’s get right down to it, shall we?

Chapter 1

Northanger Abbey starts by introducing the Morlands. They are, it is quickly established, a very normal family. The father is a clergyman, and the mother has good sense and a good constitution. Our protagonist Catherine is the first daughter of a family of ten, and is cheerfully average. She likes sports, is not particularly intuitive, and has none of the more romantic accomplishments one might expect: Music, drawing, looking after sick relatives, she fails at them all. As she enters adolescence she becomes a little prettier, a little less wild. It becomes clear that nothing of note will happen to her in her little town, and so she is whisked off to visit Bath with resident kooky older aunt figure Mrs. Allen.

Chapter 2

The voyage to Bath passes without complication, and Mrs. Allen is shown to be a perfect companion to a teenage girl: She has an adolescent enthusiasm for parties and pretty dresses, and wastes no time getting Catherine all kitted out for Bath social life. Once Mrs. Allen has gotten her fill of shopping, it’s off to the Upper Rooms! (My edition of the novel informs me that this was a well-to-do building that held balls four nights a week, which frankly sounds exhausting, but I’m a grump so what do I know.)

The hall is uncomfortably crowded, and poor Ms. Morland is unable to dance, for she has no acquaintance in Bath. I’m pretty sure we can all relate to feeling awkward at a party where we don’t know anyone, but at least these days etiquette doesn’t bar us from introducing ourselves to fellow revelers, at least in theory. Eventually the night ends, but it isn’t a complete wash for Catherine. She overhead a couple young fellows call her pretty.

Chapter 3

Things continue in the same isolated way, until one night Catherine makes the acquaintance of a certain Mr. Tilney. He is described thusly: “[he] had a pleasing countenance, a very intelligent and lively eye, and, if not quite handsome, was very near it.” Attention folks! We now have our first contender for the role of Love Interest! This is not a drill! Real talk though, Tilney has a great sense of humour, and always succeeds in ingratiating himself to me. Just listen to how he self-deprecatingly talks about how he’ll appear in Catherine’s diary:

“Yes, I know exactly what you will say: Friday, went to the Lower Rooms; wore my sprigged muslin robe with blue trimmings – plain black shoes – appeared to much advantage; but was strangely harassed by a queer, half-witted man, who would make me dance with him, and distressed me by his nonsense.”

BRB, just collecting myself from off the floor. There will come a time when Tilney’s teasing becomes just the tiniest bit condescending, but we’ll cross that bridge later, for now he’s charming and lovely and very lovable. He wraps Mrs. Allen around his little finger with his knowledge of fabrics (hurrah for gender role-defying interests!) and dances again with Catherine. The evening ends well, and Mr. Allen (who does not a whole lot all book long) very adorably makes sure that Tilney is an appropriate contact for Catherine.

Chapter 4

The next day, while out on the town, Catherine is eagerly looking out for Mr. Tilney. He is, unfortunately, nowhere to be found, but she does make the acquaintance of one Isabella Thorpe. Proving what a small world they live in, Catherine’s older brother James befriended a Thorpe son in college, and met the whole family over Christmas holidays. After much courteous small talk, Isabella and Catherine take a turn around the room. (I’d like to bring this back, it seems so wonderfully ridiculous to be parading arm in arm around in a circle.) They talk of balls, fashions, and flirtations, and Isabella, being four years older, has many things to say on each of the subjects. Catherine has a new BFF.

Chapter 5

That evening and the next day, Catherine and Isabella become increasingly inseparable, and Tilney is still AWOL. This air of mystery further intrigues Catherine, naturally. This chapter ends up being a little thin on plot, because Austen takes several pages to defend novels, the work in which “the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best chosen language.“ Unlike many gothic writers, Austen will allow her female characters to read and enjoy novels, and no critic or genre convention will stand in her way.

Commentary

Right off the bat we know that this isn’t going to be your average gothic novel. Catherine isn’t orphaned, mistreated, or under the thumb of vicious family members. There’s nothing dire or dramatic about her. This isn’t conjecture; we are told upfront that she is still “in training for a heroine.” The potential may be there, but so far it is tragically untapped.

Speaking of potential, one of the overarching themes of the book is how Catherine, an avid reader of larger-than-life novels, learns to be a reader of people, of real life. We see her go from a very naïve, easily manipulated girl, to someone with the self-possession and social acuity to see people for who they truly are. This kind of insight can only be achieved with lots of social interaction, so it’s off to Bath we go!

Catherine will be leaving the safe confines of family life, and braving the perilous world of one of the large cities Austen so hated. It’s telling that in satirizing a genre dominated by drafty castles and ghostly moors, most of Northanger Abbey’s danger happens in Bath. Austen isn’t so much concerned with age-old secrets and dashing bandits as she is the affected insincerity of city life.

We are also, quite early on, provided with Austen’s unambiguous opinion on novels. Though we are told that Catherine will only read if the book provides “nothing like useful knowledge” and is “all story and no reflection,” Austen clearly loves novels. They were, in her time, considered a lower form of literature, fit only for silly women and the not very bright, but Austen loves them nonetheless. She loves them enough to break off her story for an unapologetic tangent, in which she addresses the reader directly, claiming solidarity with other authors and basically informing us that novels are the best and haters gonna hate. She is a novelist, and her protagonist will love novels as well. Austen will not be performing self-hatred, no matter what pressures are exerted by conventional (meaning male) literary authorities.

Novels and femininity then seem inextricably linked, and Austen has never been disdainful of girlishness. Even the titling of her books betrays how close her female protagonists are to her heart. Between Emma, Sense & Sensibility’s original title “Elinor and Marianne,” and Northanger Abbey’s early draft being titled “Catherine” (and “Susan” before that), Austen’s women are of central importance. Though she may tease her young subjects, Austen is delighted by the silliness of them. Whether they’re changing their names in a fit of adolescent drama, or absurdly pleased to be called pretty, she understands them and treats them gently. And if Austen advocates for a love of novels tempered with good sense and practicality (a journey Catherine will hopefully make), then stereotypical girlishness too is harmless when there’s wisdom to back it up.

—

That’s all for this week! Stay tuned for chapters six through ten, wherein we meet Henry Thorpe, and Mr. Tilney makes a triumphant (and totally unexpected) return!