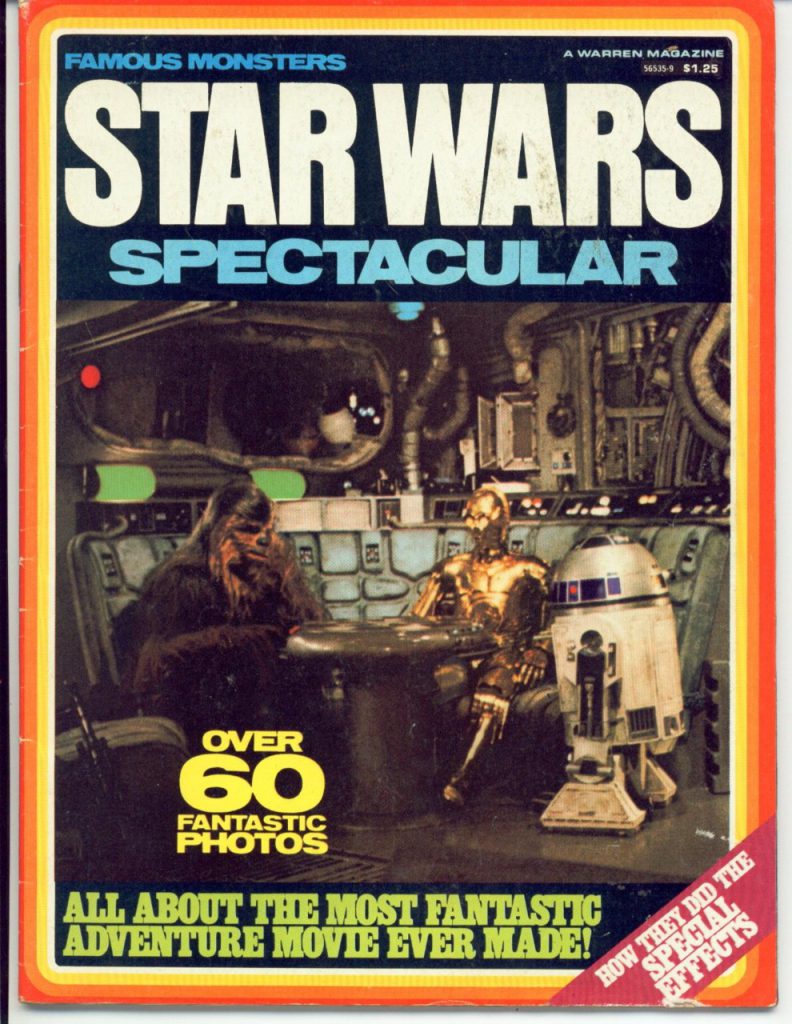

Books We’re Thankful For: Famous Monsters of Filmland’s Star Wars Spectacular

When I was a kid, I read A Wizard of Earthsea, and I read The Hobbit, and I read The Great Brain, and The Saturdays, and From the Mixed Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, and I read Judy Blume, and I read pretty much everything I could get my hands on, from Choose Your Own Adventure to the Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom novelization, but there is only one book that I look back and am truly thankful for. It’s the book that saved me, the book that made me who I am today, the book that turned me into a writer. It is, of course, Famous Monsters of Filmland’s Star Wars Spectacular.

I inherited the magazine from one of my older sisters and it was already battered when I got it, but even creased and stained and with the staples ripped out, it still promised to tell me “All About the Most Fantastic Adventure Movie Ever Made!” A padded-out promo rag printed on pulp paper designed to cash in on the Star Wars craze, it’s barely 50 pages long, slathered with black and white stills from the movie that its cheap paperstock turn into grainy, high contrast Weegee snaps.

The first six pages are a gallery of characters, filled with stilted, grandiose text that was electrifying to my eight-year-old eyes. Luke Skywalker “…takes off for outer space to increase the pace of his living.” Grand Moff Tarkin possessed the Death Star that is “capable of volatizing an entire planet!” They were larded with references I couldn’t understand but that hinted at a bigger world around me. Harrison Ford “has 2 sons, Willard & Benjamin — reminding one of a double horror bill of several seasons ago!” It does? Tell me more!

There’s a short section about the special effects written in a kind of telegraphic Variety shorthand (“Miracles! The filmagicians have been performing them before our startled eyes!”) then a synopsis of the movie dripping with purple prose (“They have survived the Star Wars with flying colors. The stars now are in their eyes and the eyes of the Princess. Most of all, the stars are in the eyes & the ears of the universally dazed audiences.”) and then came the most important section of all: “The Best Science Fiction Film Ever Made.”

In the days before VCRs, it was impossible for a kid from South Carolina to see old movies, and here were fifteen I’d never heard of, boiled down to short, 200-word descriptions that were little more than punchy lists of marvels, like some kind of word-drug injected right into the base of my brain. The Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe entry read, in its entirety:

“The Buster Crabbe serials.

Featuring almost more marvels than the human mind can remember:

The Sharkmen of the Underwater Kingdom.

The Tree Men of Mars.

The Octosac…the Gocko…the Clay Men.

The Hydrocycle, the Spaceograph, the Gyroships, Nitrogen Ray Machine.

The Lion Men. Hawk Men. Monkey Men.

The City in the Sky…The Bridge of Light.

The invisibility ray…the tigrons…the fire dragons…the zebra-striped bears…

The magic of Azura!”

So many nouns hinting at so many things! No connective tissue, no boring plot, no tedious story, just one amazing thing I’d never heard of after another, flying at my face as fast as I could read. They covered Planet of the Apes (“The mummified astronaut!”), Silent Running (“The toggles, the monitors & the waddling droids.”), This Island Earth (“The war with Zahgon…the guided meteoroid missiles…the splendid saucer ship.”), and, most amazing of all, Metropolis (“The incredible Super City of 60 million. The Massive Underground Machinery of Moloch. The Human Clocks…the Old Dark House of the anachronisitcally alchemical genius…The submergence of the subterranean city. The flames consume the Metal Maiden.”).

I had no idea what they were talking about, but I wanted some. I didn’t need to see these movies, I just studied their descriptions until I knew them by heart. I knew that 2001: A Space Odyssey was about a starship full of hibernating space vampires. I knew that Things to Come was about a war between underground mole men and surface dwellers who were addicted to PBS. Buck Rogers was about space fighters in blimps getting mail order rayguns and robots out of a catalogue and, also, something about scuba diving.

With no access to these movies, and not allowed to see anything rated R, I began convincing adults to buy me movie magazines like Fangoria, reading about movies I would never see, making up the plots in my head, tossing off phrases like “Atomigeddon” and “The Sphinx of Far Futurity” the way other people talked about “beach towels” or “grapes.” Years later, I finally saw 2001: A Space Odyssey and was disappointed and confused that there wasn’t a single space vampire in sight. Reality didn’t live up to the dreams I got from this cheap, crummy chunk of newsprint.

And that’s when I realized that if I wanted to see those stories, I’d have to write them myself.

Grady Hendrix

Grady Hendrix is an award-winning novelist and screenwriter living in New York City. He is the author of several New York Times bestsellers including How to Sell a Haunted House, The Final Girl Support Group, The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires and many more. His books have been translated into more than twenty languages and sold over two million copies. He also writes non-fiction and his history of the horror paperback boom of the seventies and eighties, Paperbacks from Hell, won the Stoker Award for Outstanding Achievement in Nonfiction.