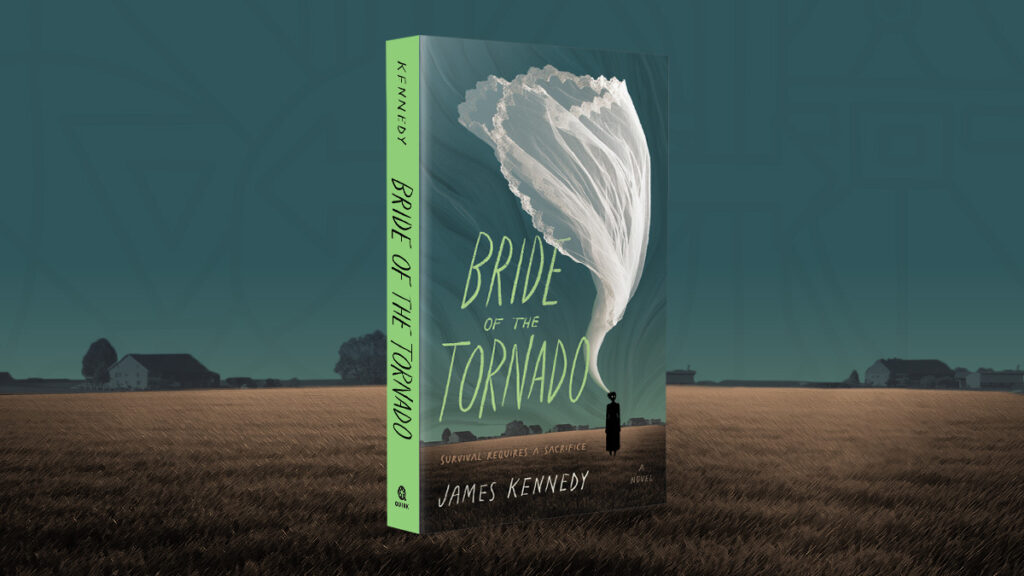

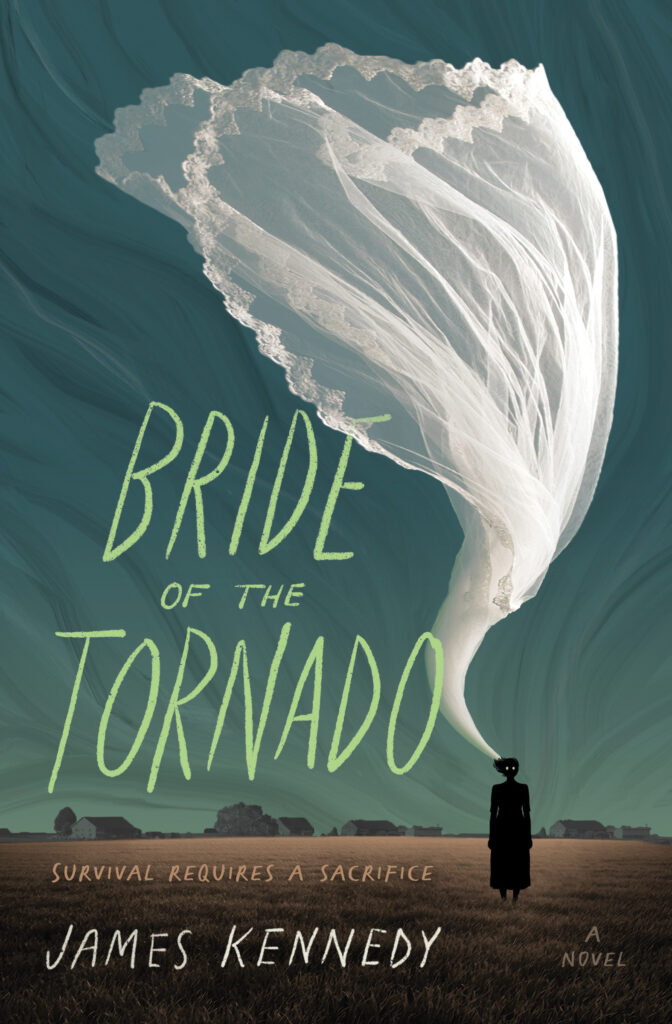

James Kennedy’s Five Midwestern Horror Novel Picks

I grew up in Michigan and I’ve spent most of my life in the Midwest. When I began writing my horror novel Bride of the Tornado, one of the things I had in my mind was an October night in the 1990s, when my wife-to-be Heather and I headed out to rural Indiana to visit a “haunted house.”

It was farther away from town than we thought. When we arrived, we found just a few train cars in a desolate field. No other visitors. A creepy girl played with some dolls in the grass. After a minute, she got up and gravely led us through the train cars. A family sat around a table, greeting us indifferently as we passed. Did they live here? Who knew? These train cars were full of homemade oddities, more quirky than spooky. A bucket of plastic body parts. A cheesy mechanical doll. It was awkward and low-rent, not scary.

Then a maniac jumped out of nowhere with a chainsaw.

We screamed and ran. I hadn’t learned yet that Heather’s reaction to being scared was to laugh, and she laughed uncontrollably as we ran. After chasing us for a while, the chainsaw man came to a halt, shrugged, and shuffled off. The girl nodded to us. The tour was over.

The experience was very Midwestern. Low-key and unassuming. A middle-of-nowhere feeling. Workmanlike production values. Laconic. An isolated location with a small group of weirdos that began to feel inescapable. The people closest to you acting bizarrely. An apparent lack of a reason for things.

For me, horror set in the American Midwest feels distinct from horror from other regions: different than the stern eldritch witchiness of New England horror, the overripe kinda-sexy feel of Southern Gothic horror, and the dead-eyed psychosis of California horror. It’s a humbler mood, and that modesty has its own odd power.

These five books of Midwestern horror have made an impression on me over the years.

Something Wicked This Way Comes by Ray Bradbury

I first read this book when I was twelve. Bradbury’s setting of “Green Town, Illinois”—a romanticized version of his boyhood home of Waukegan—was strange enough for me to feel intrigued, but similar enough to my own suburban Michigan hometown to feel familiar.

The book is about two 13-year-old friends: the adventurous Jim Nightshade and the more obedient Will Holloway. A haunted carnival comes to town, and its malevolent crew—a man covered with tattoos, a blind witch, a skeleton creature, The Most Beautiful Woman In The World—lure normal-but-disheartened townfolk with false promises of youth, glamor, and love, while actually transforming them into fresh freaks. Brash Jim is tempted by the allure, but it’s Will and his sad-sack-turned-hero father (the town library’s janitor) who save him and break the carnival’s power.

Jim and Will exemplify the two warring urges of many young Midwesterners. Jim is the frustrated impulse of “I’m stuck here, I won’t amount to anything if I stay!” and Will personifies the desire of “Why can’t everything just stay the same?”

Bradbury is at his best when he takes the things he loves—like small town life—and makes them menacing. The scene where Jim and Will hide from the carnival’s ringleader in the library stacks is particularly terrifying.

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

Wait, I’m characterizing In Cold Blood as “horror”? Isn’t it rather the book that launched the modern True Crime novel? Or the first “nonfiction novel”? Yes, but it’s also scary as hell, and its uneasiness has stayed with me longer than many horror novels.

Herb Clutter was a well-off farmer who lived in an isolated house on the western Kansas plains with his wife and kids. Going off a jailhouse tip that the Clutters had lots of cash, two ex-convicts traveled 400 miles across Kansas, snuck into the unlocked farmhouse, and murdered the family. And for nothing: there was little of value in the house. The rest of the book is about the details surrounding this particularly pointless murder: the life stories of the criminals and victims, the dead ends of the investigation, the wanderings of the criminals, and the coincidences that led to their capture and execution.

I remember being disturbed by In Cold Blood because of the arbitrary nature of the crime—one cockeyed tip by an unreliable cellmate led two men to drive hundreds of miles to kill a family they didn’t know. The crime was committed when Eisenhower’s interstate highways had only recently connected far-flung places, making it much easier for distant strangers to arbitrarily erupt into one’s life. The isolation of the Clutter household in the hugely empty Midwestern landscape was chilling: there was no one to hear their cries, no one to help. But maybe the most disturbing thing is the “Midwestern nice” of the murderers. As one of them said about Herb Clutter, “I didn’t want to harm the man. I thought he was a very nice gentleman. Soft-spoken. I thought so right up to the moment I cut his throat.”

Rotters by Daniel Kraus

When ordinary teenage boy Joey Crouch’s mother is killed in a bus accident, he must move from Chicago to small-town Iowa to live with his estranged father Ken Harnett. Joey’s noxious-smelling father is a town pariah, and so of course Joey is relentlessly bullied at his new school too. Joey soon learns his father’s secret occupation, though: grave robber. Reluctant but fascinated, Joey joins his father in digging up bodies and pawning their valuables. He discovers he has a knack for it.

And that’s when the book begins to get gloriously, unrepentantly gross.

We are treated to scene after disgusting scene of digging up bodies; we learn about details of the trade such as “coffin liquor,” the goo that results when a corpse liquifies over time; Joey even gets inducted into the secret society of old-man grave robbers who believe they uphold a righteous tradition. Come for the writhing maggots, rat kings, and distended corpses—stay for the unconventional father-son story.

Kraus grounds the grossness of his story in the ordinary landscapes, shabby architecture, and routine minutiae of Midwestern life. Having grown up in Iowa, these details must come from Kraus’ experience—and possibly taps into his suspicion, too, that there is something macabre happening secretly underneath all this agreed-upon normality.

Ill Will by Dan Chaon

Much of Midwestern horror lives in the silences: what is not talked about, what is not seen, what is not remembered—and how those silent things nevertheless manifest themselves, breaking through even the hardiest Midwestern conflict-avoidance, inarticulateness, and polite conventions. In Ill Will, Chaon writes around those disquieting gaps such that by the end, he doesn’t have to spell out the horror that awaits.

Set in charmless modern-day suburban Ohio with flashbacks to bleak 1980s flatlands of Nebraska, it’s about a middle-aged hypnotherapist Dustin Tillman—distracted father to two college-aged sons, and soon about to lose his wife to cancer. There’s a dreamy, waffling vagueness about Dustin that feels very Midwestern to me. He often trails off before he finishes his sentences, he turns a blind eye to difficult truths in order to smooth over his relationships (he doesn’t notice his son is becoming a heroin junkie), and he fecklessly lets an eccentric patient walk all over him. Maybe it’s because of Dustin’s horrific past: in 1983, his mother, father, aunt, and uncle were all murdered, seemingly by his adopted older brother Rusty, a wannabe Satanist and charming bully. When the story opens forty years later, DNA evidence has exonerated Rusty and he is freed, to Dustin’s alarm. Bodies start piling up, and Dustin is beguiled by his ex-cop patient into playing investigator on the seeming serial murders. Hopping between multiple plotlines and narrators, it becomes clear our characters are sleepwalking into a monstrous fate . . . and yet that fate is left tantalizingly undefined to the end of the book, and perhaps even beyond. Chaon effectively describes the humdrum dreariness of middle-class-slipping-into-squalor, and you’ll find yourself both sympathetic to and repulsed by Dustin, a narrator so unreliable that he is unreliable even to himself.

Universal Harvester by John Darnielle

The premise is straight out of early-aughts horror. It’s the 1990s, and Jeremy works at a video store in small town in Iowa, where customers begin complaining about the videotapes they’re returning: “There’s something on it.” Jeremy’s floating through life, living alone with his father in the aftermath of his mother’s death (see a recurring theme?). Teaming up with his livelier friend Stephanie, Jeremy reluctantly investigates the origin of the eerie spliced clips in the movies—some of which seem to have been recorded right in town.

What promises at first to be a Blue Velvet-esque mystery unexpectedly shifts gears. We’re hurled back into the 1970s, when a seemingly normal wife and mother in small-town Iowa vanishes into a garbage-eating Christian cult; and then we leap forward again to present day, when a family finds in their new house a collection of weird videos that hold the key to the mystery.

Or not quite. Darnielle—of the indie band The Mountain Goats—leaves much intriguingly unresolved. This may irritate some, but this is exactly what will keep me thinking about this book. And though it was the spooky premise that hooked me, it was the evocation of small-town Iowa life that kept me reading. The reticent but deep relationship between Jeremy and his father, the sweet courtships, the earnest and only intermittently successful efforts to connect—all are rendered in a way that credits midwestern modesty and reserve. What starts as a horror story transforms into something more mournful, recognizing the satisfactions of small-town life while remaining clear-eyed about loneliness and grief. In Darnielle’s generous telling, we understand the dignity of staying in a stifling situation because of one’s own inertia and obligations to others; but we also understand why some must simply run.

If you pick up Bride of the Tornado, maybe you’ll see why these books appealed to me. I hope it too evokes for you the flat, uncanny, lonely register of Midwestern horror.