How to Win the War on Banned Books: Author Samuel C. Spitale on Censorship and the Questions Readers Should Be Asking

When I was in junior high, I wanted to read Carrie Fisher’s first novel, Postcards from the Edge. So for Christmas, I asked my mom for the book.

My mom, however, didn’t think that was an appropriate gift for a 13-year old. She’d heard that the book was an unflinching look at Fisher’s drug addiction. Concerned about such undue influence, she did not want me to read it.

That decision did not sit well with me, so I checked out the book from the local library and read it in secret.

The book did not inspire me to become a drug addict, nor did it pique my curiosity about drug use. But it did generate an enormous amount of empathy for Fisher’s alter ego, who struggled to reclaim normality after a harmful bout of drug addiction that necessitated a stint in rehab. Drug use was portrayed as anything but glamorous. But that’s rather beside the point.

The point is that I read the book anyway, despite parental reservations. I just didn’t tell my mom that I read it.

And there we have one of the problems with—and futility of—trying to ban books. Prohibition of any kind doesn’t dampen the prohibited desire. It just makes one more adamant to engage in prohibited behavior. Just ask all the Mafiosos who got rich off prohibition when alcohol was banned in the 1920s. People didn’t stop drinking liquor. Liquor just went underground. (Legislatures trying to ban abortions would be wise to heed this lesson.)

Book banners, it seems, suffer from a similarly myopic account of history. In 2021, PEN America—a nonprofit committed to preserving free expression in both the U.S. and abroad— found more than 1,500 cases of book banning in the U.S., spanning over half the states in the nation. Texas leads the pack with more than 700 restricted books, including a graphic novel of Anne Frank’s Diary.

In the past year, book banning has spread like wildfire—so much that Margaret Atwood released a fireproof copy of The Handmaid’s Tale, which was auctioned by Sotheby’s for a cool $130,000 to raise money for PEN America.

The American Library Association keeps a list of the most banned books for any given year. The patterns are fairly consistent. Many are books that shine a light on racism (The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas, Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by Ibram X. Kendi and Jason Reynolds, and Something Happened in Our Town: A Child’s Story About Racial Injustice by Marianne Celano, Marietta Collins, and Ann Hazzard) or depict experiences from the LGBTQIA+ community (Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe, This Book is Gay by Juno Dawson, and All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson).

Books like these are powerful because they—like Fisher’s semi-autobiographical novel—are empathy generators. Empathy is the ability to put ourselves in someone else’s shoes, to identify with someone else’s struggle as if it were our own.

As humans, we are biologically geared for empathy. Our mirror neurons help us mimic emotions in others, allowing us to feel what they feel—even if those others are characters in a story. When watching a horror film, we can feel the same fear as the heroine peering around a dark corner in a creepy house. In a love story, we can feel the same sense of loss when a beloved character passes away.

Stories allow us to empathize with people who are different from us, activating our mirror neurons and connecting us emotionally so that we can appreciate what unites us: the highs and lows of the human condition. They can make us feel for people who live different lives, in different skins, as different genders, in places geographically far away, or several lifetimes ago.

Stories are unifying and that’s why books can be so threatening to existing power structures in the midst of a changing world.

Banning books has always been a means of control. It’s not about avoiding an uncomfortable conversation (as with Postcards from the Edge), but about limiting access to a diverse array of voices and ideas that some feel threatened by. It’s a way to squelch dissent, discourage independent thought, and to limit social change, making us more susceptible to propaganda in the process.

By silencing those who threaten the established order, we discourage others from raising their voices. By denying people a voice, we prohibit others from identifying with them. And for those simply trying to tell their stories, we deny them empathy.

This is why representation matters—and why the people in power will continue to fight it every step of the way.

One way to fight book bans is by reading challenged books, to understand why that book was targeted and what that author is trying to say. Ask yourself why the people in power feel so threatened by that book’s message? Does it seek to make us aware of racial injustice? Does it seek to help us understand what it’s like to be gay or bisexual? Does it challenge our perspectives on an issue?

Censorship has long been anathema to the First Amendment, which enshrined the freedom of speech into U.S. law. Those who censor speech are not doing so out of a sense of parental protection. By banning books, they are deliberately trying to control a populace, limiting their perspectives, their voices, and their ideas, with the goal of rendering them less informed and ultimately less empathetic to those unlike themselves.

These measures are part of a systematic war on truth, an effort to control the flow of information and limit people’s knowledge. Because the less informed we are, the more susceptible we are to manipulation, as anywhere knowledge is lacking, propaganda offers to fill the gap.

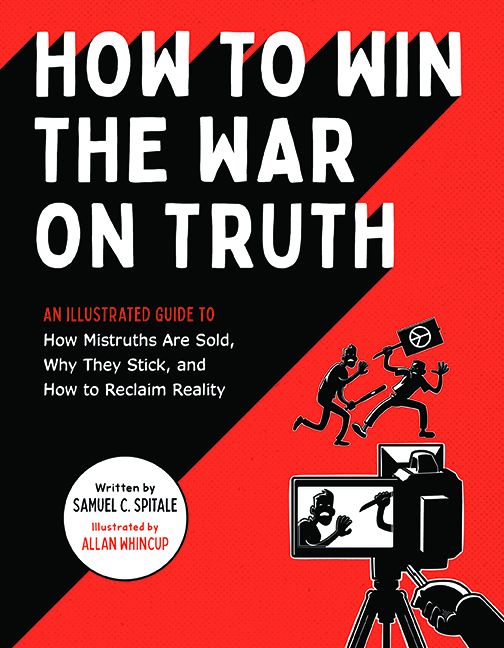

Learn more about the history of propaganda, who profits from it, and how to find the truth for yourself in my book How to Win the War on Truth: An Illustrated Guide to How Mistruths Are Sold, Why They Stick, and How to Reclaim Reality, on sale October 25, 2022.

Preorder the Book

Samuel C. Spitale

Samuel C. Spitale is a media studies expert who has written for Huffington Post, as well as Geek magazine and Advocate.com. Previously, he worked at Lucasfilm Ltd. in global product development. He is the author of Star Wars: Collecting a Galaxy.

Allan Whincup is a former art director who works as a freelance illustrator and designer. His projects include logo design, character design, storyboarding, and creating assets for animation. He has also worked on games, CD covers, and comics.