Dare to Know author James Kennedy’s “Damn Fine” Thoughts on David Lynch

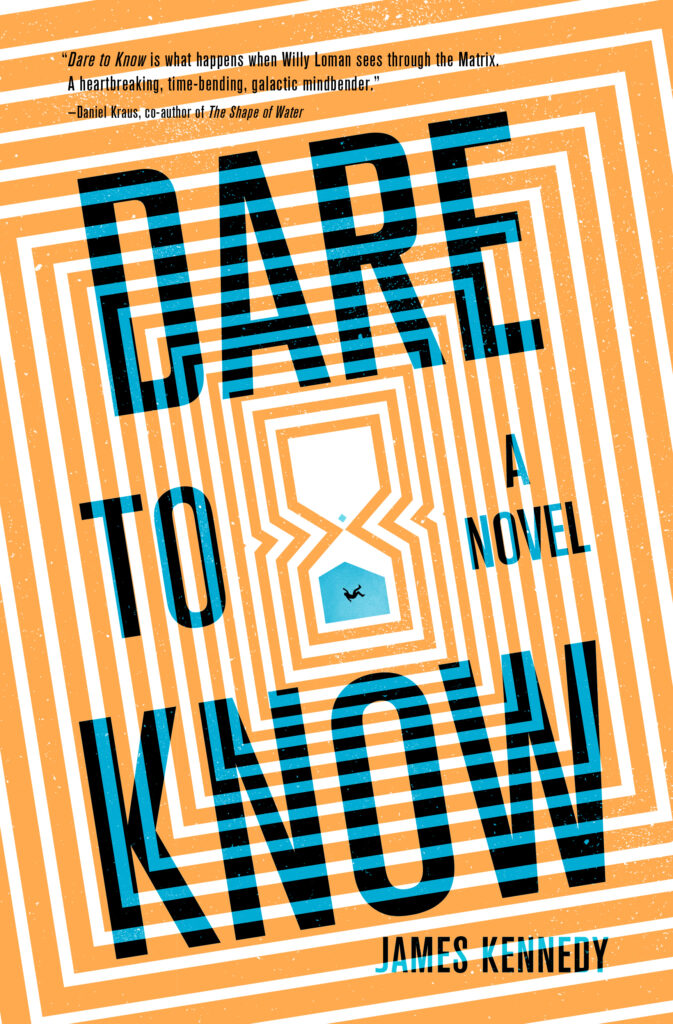

I’ve been a fan of David Lynch ever since high school, when I recklessly watched a VHS of Eraserhead alone at one in the morning. Such an experience leaves its mark. As it turns out, my latest novel, the speculative thriller Dare to Know—about a company that can calculate the precise time of one’s death with perfect accuracy—has been described as “Lynchian.” Cool!

But what does “Lynchian” really mean? David Foster Wallace tried to define it as the “irony where the very macabre and the very mundane combine in such a way to reveal the former’s perpetual containment within the latter.” (Pretty fancy talk for a guy who kept doing a running joke about Depend adult undergarments in Infinite Jest.)

But there’s more to Lynch than just that macabre/mundane tension, DFW! Instead of one totalizing formula, I feel there are several distinct tendencies that recur in Lynch’s work—and yeah, some of those tendencies also show up in Dare to Know.

So settle in with your coffee and cherry pie—or garmonbozia, if you’re hardcore—and let’s look at what makes something Lynchian.

“The owls are not what they seem.” The supernatural shouldn’t make too much sense. When we encounter the Black Lodge in Twin Peaks—with its backwards-talking dwarf, red velvet curtains, black-and-white chevron floor—it’s striking not only because of the imagery, but because those scenes resist having direct storytelling value.

Actual dreams don’t make sense! The whole point of the supernatural is that it overflows and breaks the normal! And so, when the weird erupts into everyday life—whether it’s the Black Lodge in Twin Peaks, or Robert Blake’s Mystery Man in Lost Highway, or the porous dreams of Mulholland Drive—it’s good that such weirdness can’t always be cashed out narratively in a neat correspondence with the plot. That would make it stop feeling dreamlike. True Lynchian weirdness says both too much and not enough.

Some folks get frustrated and say, “Lynch is just being weird for the sake of being weird.” Nah. These scenes feel like have their own logic, even if we can’t say what it is precisely. In Dare to Know, I wanted dreams and visions to function the way they do in a Lynch film: they aren’t just a metaphor for the “real” world, they constitute their own world with its own enigmatic rules.

“Where we’re from, the birds sing a pretty song, and there’s always music in the air.” There’s something haunted about old pop songs. Lynch has said that it was Bobby Vinton’s song “Blue Velvet” that inspired his movie of the same name. Similarly, Dare to Know was inspired by the Beatles song “You Know My Name, Look Up The Number”—indeed, that my original title for the book.

But that’s not the only dated pop song that Lynch has featured in his work. There’s the classic scene in Blue Velvet where Dean Stockwell serenades Dennis Hopper with Roy Orbinson’s “In Dreams.” Or how The Platters’ “My Prayer” figures into the gruesome “Gotta light?” scene in Twin Peaks: The Return.

Obviously, Lynch isn’t the only director to feature oldies in his movies. But he recontextualizes these songs in a peculiar way. I think he recognizes that there is something unsettling about old pop songs, which after all, are meant to be ephemeral. As time goes by, and the era of certain pop songs recedes, those songs can begin to sound strange, stilted, or outright menacing.

It’s kind of like when you hear an old laugh track on a sitcom, and then someone informs you that by now, all those people laughing are certainly dead. In Dare to Know, I go back to 1980s Top 40 hits to excavate their creepiness in the same way. I promise you’ll never hear Don Henley’s ominous “Boys of Summer” or Madonna’s insect-like “Into the Groove” the same way again.

“When you see me again, it won’t be me.” Slippage and/or loss of identity is common in Lynch’s movies and TV. Sometimes Leland Palmer is Killer Bob. In Twin Peaks: The Return, Special Agent Dale Cooper fractures into doppelganger Bad Coop, tulpa Dougie Jones, and parallel-reality “Richard.” In Lost Highway, Bill Pullman’s character goes to sleep in prison, only to wake up as a completely different character played by Balthazar Getty. And who can untangle the identities of Naomi Watts’ Betty Elms / Diane Selwyn and Laura Harring’s Rita / Camilla Rhodes in Mulholland Drive?

In Dare to Know, identities are similarly elastic. But having personalities seem to migrate from one character to another isn’t a card you should play too early in the story. Only after starting the story on a clear and firm footing, and then gradually turning up the weirdness, can you get away with this kind of move. But when it works, the effect is powerful and haunting—and it has a specific truth to it. After all, do you always feel like “yourself”? And how many times has someone close to you done something that makes you realize that they aren’t the person you thought they were at all? Identity is more unstable and shifting than conventional stories have capacity for.

“We are like the dreamer who dreams, and then lives inside the dream. But who is the dreamer?” So says Monica Bellucci (in a dream, natch) to FBI Deputy Director Gordon Cole in Twin Peaks: The Return. Often in Lynch’s work it’s not clear what is reality, what is a dream, and who is generating the dream—is the second half of Lost Highway a dream-fantasy that Bill Pullman’s character is having while on death row? Is the first half of Mulholland Drive a dream-fantasy that Naomi Watts’ character is having out of guilt for having caused the death of her lover? And in Twin Peaks: The Return, is the entire world a dream of Lynch’s stand-in character, Gordon Cole? Or Dale Cooper?

I don’t want to spoil the ending Dare to Know, or over explain its mysteries, but its ending pivots around two characters who create a universe of dreams between them, and come to mistake those dreams for realities—and we then see how these dreams can become real, even as the dreamers fade away.

“I have no idea where this will lead us, but I have a definite feeling it will be a place both wonderful and strange.” I didn’t understand the end of Twin Peaks: The Return, even though I felt on some level it made sense—and that’s why I will keep thinking about it until the day I die. Similarly for Mulholland Drive, Lost Highway, and Inland Empire. They aren’t puzzles to be cracked, but rather, fertile zones for interpretation. (Save me your meticulously worked-out theories—none of them truly capture the mystery.) Lynchian mysteries aren’t meant to be solved, but rather to be lived in.

About Eraserhead, Lynch said that not a single reviewer of the film understood it in the way he intended. That is comforting. I don’t want the mysteries of Lynch’s movies to be cleared up, I want to live in those mysteries and let them accompany me through my life. And if somebody feels the same about the mysteries in Dare to Know, then I will feel I have done my job.