Craziest Things That Have Happened at Political Conventions

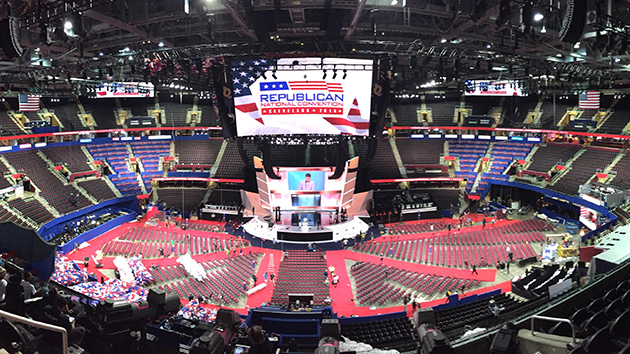

I'm waiting to see if something outlandish happens before the end of the Republican National Convention. Not violence in the streets—but a political spectacle of the type that used to run the engine of national elections in this country. Because, you see, Virginia, there actually used to be interesting presidential nominating conventions in America, not merely pre-fabricated media opportunities for candidates with canned messages.

Since their inception in the early 1830s, national conventions were intended to be expressions of our collective psyche and temperament. Sure, most candidates were picked in smoky back rooms, but the will of the people was felt as a force to be reckoned with. Back then, up to 90% (in some cases) of eligible voters actually went to the polls.

And conventions were the nexus of their hopes, dreams, fears, and passions.

When the Republicans met in 1860 at Chicago’s famed Wigwam—a massive, two-story, block-long building on the banks of the Chicago River—William Seward, former governor of New York, was the favorite. But backers of former Illinois Congressman Abraham Lincoln waited until Seward’s delegates were marching in demonstration around the convention hall and then distributed counterfeit tickets to other Lincoln backers waiting outside. When Seward’s men returned, they found they could not get back into the building to vote.

When the voting began, ten thousand people were inside the hall, with another twenty thousand screaming and chanting on the streets. One observer described the noise inside: “Imagine all the hogs ever slaughtered in Cincinnati giving their death squeals together, plus a score of steam whistles going.”

After four rounds of balloting, the vote went to Abraham Lincoln.

Then there was the infamous 1924 Democratic National Convention in New York, one of the craziest on record, where the nomination of the colorless John Davis seemed merely an afterthought. The Democrats were going to lose that year (Davis would be defeated handily by Silent Cal Coolidge), but it was the convention itself people remembered. 103 ballot, the most in history. Twenty thousand Ku Klux Klansmen, wearing hooded robes, burning crosses on the bluffs of New Jersey, in support of Davis’ rival William McAdoo. Brawls on the convention floor (some people came armed, just in case).

Or how about wonderfully ridiculous Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia in July of 1948, the first ever to be televised, although on the east coast, only. (Both parties held their convention in Philadelphia that year, because the city was located on the Boston to Richmond coaxial cable that carried television up and down the coast.) Cables ran over the convention floor while batteries of hot lights arched over the stage (in the non-air-conditioned hall, the temperature at the podium was 93 degrees). Speakers wandered around wearing thick pancake makeup (women were told that brown lipstick showed up better on black-and-white television sets, so most female orators looked like they’d just bitten into a big piece of chocolate).

At two in the morning, when Harry Truman was about to go onstage to accept his party’s nomination, a flock of pigeons was released from a huge floral Liberty Bell suspended from the ceiling. The birds, who had been trapped all night in the hot and humid bell, went berserk. In a scene straight out of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, the pigeons began dive-bombing delegates, smashing into the rafters of the hall.

After a moment of stunned silence, Truman and everyone in the hall broke into uproarious laughter. The few people awake and still watching were privileged to see one of the most wonderful moments of live television ever recorded.

Is there a threat of violence in Cleveland? Possibly. But we’ve handled that before. In 1912, when Teddy Roosevelt made this third party run at the Republicans, a group of his Rough Riders came dressed in full uniform (Roosevelt himself came wearing his floppy Rough Rider hat) and stormed into the Chicago convention hall to try to keep party bosses from re-nominating President William Howard Taft. Barbed wire was strung around the convention stage, 600 police officers with billy clubs guarded the hall, and newspapers warned of violence and anarchy. None of that happened.

Despite the dire warnings of the downfall of the American republic that we keep hearing, the sure-to-be-fractious Cleveland convention is squarely in the American tradition, much more so than the homogenized media productions we’ve seen from both parties in recent years.

When the Republicans meet in Cleveland, one can only hope for a little spectacle. Or, as the great American writer H.L. Mencken once put it, when writing about national conventions, a little something “gaudy and hilarious… melodramatic and obscene, unimaginably exhilarating and preposterous.”

It would do us good.

Podcast with the author:

Joseph Cummins discusses Anything For A Vote in this podcast with HarperAudio. Give it a listen!

Joseph Cummins

JOSEPH CUMMINS has written several books of history, including Anything for a Vote (which “wonderfully chronicles the campaign smears . . . that have typified U.S. elections,” New York Times/Freakonomics blog) and History’s Great Untold Stories (“gripping stories and lively writing,” Library Journal). He lives in Maplewood, New Jersey.

JOSEPH CUMMINS has written several books of history, including Anything for a Vote (which “wonderfully chronicles the campaign smears . . . that have typified U.S. elections,” New York Times/Freakonomics blog) and History’s Great Untold Stories (“gripping stories and lively writing,” Library Journal). He lives in Maplewood, New Jersey.