Birdman: What We Talk About When We Talk About Raymond Carver

While the Oscars always highlight adaptations of books with their Adapted Screenplay category, this year’s Original Screenplay selections feature something a little unusual. Birdman arrived last fall and built up some serious and unexpected hype by the year’s end, eventually earning nine Oscar nominations, tied only with The Grand Budapest Hotel for most nominations this year. And at its center is a well-loved short story, published over thirty years ago but never adapted for the big screen.

Birdman, co-written and directed by Alejandro González Iñárritu, is not actually an adaptation – it’s an original work about an adaptation. The film portrays the struggles of a former Hollywood superstar named Riggan Thomson (Michael Keaton) as he attempts to stage a theatrical version of Raymond Carver’s short story “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love” that he’s adapting, directing, and starring in himself. It is not going as well as he’d hoped.

Carver’s story, from the 1981 collection of the same name, has become a kind of modern classic in the years since its publication, often studied in literature and writing courses in college and beyond. This is thanks, in part, to Carver’s lean and efficient prose. He doesn’t spend many words on metaphoric descriptions of scenes or explain in detail what emotions his characters are experiencing. He instead aims for a kind of sparseness and intensity. The effect can be startling at first. You might turn a page expecting some sort of resolution, only to realize that the story has already ended. Carver prefers raising questions to giving answers, and “What We Talk About…” is a great example of this style.

The story focuses on a conversation between two married couples, Terri and Mel and Laura and Nick. As they sit around a kitchen table drinking gin, they start to talk about the nature of love. The discussion sits for a while on the topic of Terri’s ex-boyfriend, who was physically and emotionally abusive. She maintains that his actions came from a place of love, while her husband disagrees. He offers an idea of true love that’s evidenced by an elderly married couple who landed in a hospital after a car accident – the husband became depressed simply because his full-body cast meant that he couldn’t turn his head to look at his wife in the same hospital room. By the end of the story, nobody seems convinced of anything, and all four characters sit in silence.

It’s a bit of a strange choice for a stage adaptation. We don’t get a chance to see the entire play that Riggan has created in Birdman, but what we do glimpse doesn’t look great. Riggan has shifted the narrative around, which might not be too bad, but he’s also expanded some of the story’s flashbacks into big, dramatic setpieces. This seems like it would work against the story’s quieter and more unsettling themes, but this is (I think!) intentional. Iñárritu wants the audience to consider those kinds of weird, bold artistic decisions and what they might mean.

Riggan is a character that wouldn’t feel out of place in many of Carver’s stories: he seems to have run out of luck, and definitely run out of money, and his relationships are in all sorts of disarray. He’s still hoping to be loved, though, and he wants to get there through his art. In the process, he does further damage to his finances and relationships, burning bridges with his daughter, his cast, his producer, and others, but all the while committed to achieving redemption when his play is finished.

Birdman suggests that there’s some connection between the love experienced by Terri’s abusive ex-boyfriend and Riggan’s desire to be loved through his art. Some dialogue from Carver’s story points to this:

“He was dangerous,” Mel said. “If you call that love, you can have it.”

“It was love,” Terri said. “Sure, it’s abnormal in most people’s eyes. But he was willing to die for it.”

Birdman doesn’t seem quite as interested in leaving these questions unanswered as Carver did. “What We Talk About…” never settles on a definition of love, or how we ought to feel about the kind of awful and destructive love it presents its readers. Birdman gives Riggan and the rest of its cast more room to answer this question for themselves and the audience, and its ending aims for more closure than the ending of Carver’s story. Whether that was a successful decision or not has been up for debate since the film’s release.

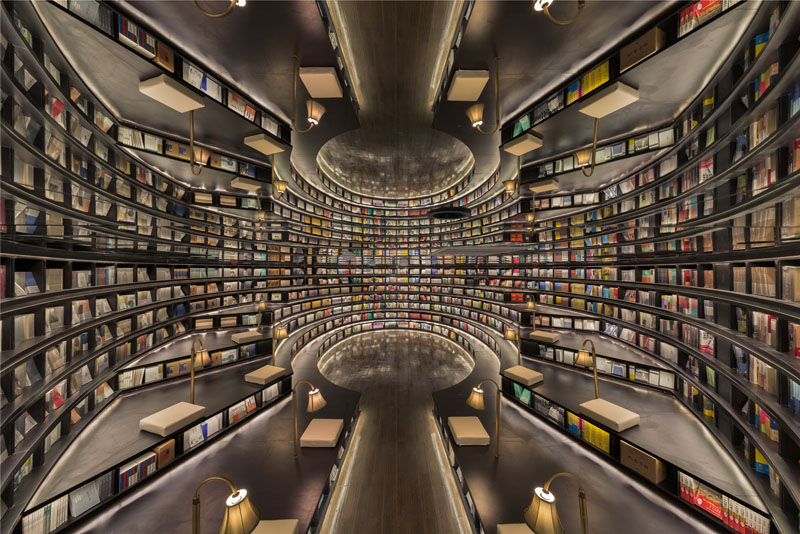

Either way, it’s always interesting to look at the spaces that exist between books, movies, and theater. All of these forms are constantly in dialogue with each other, whether through direct adaptations or indirectly, as in Birdman. Whatever wins or loses, and whatever we felt deserved to win or lose, we can be glad for the chance to revisit some great writing.