100% That Witch: The Inspiration Behind Toil and Trouble

When exactly did the word “witch” become a label one wears with pride?

Today, the word evokes images of power and success, emblazoned on everything from mugs lining the shelves of Target to Instagram and #WitchTok posts. What was once a pink glittery “girl boss” in loopy font is now “100% that witch” in glittery black loopy font. The message is the same, though. This is a woman who has her life together and is doing all the things.

The witch: she’s having a moment.

But that wasn’t always the case. In our not so recent past, a woman who was called a witch was often ostracized, or worse, in the case of the witch trials, executed.

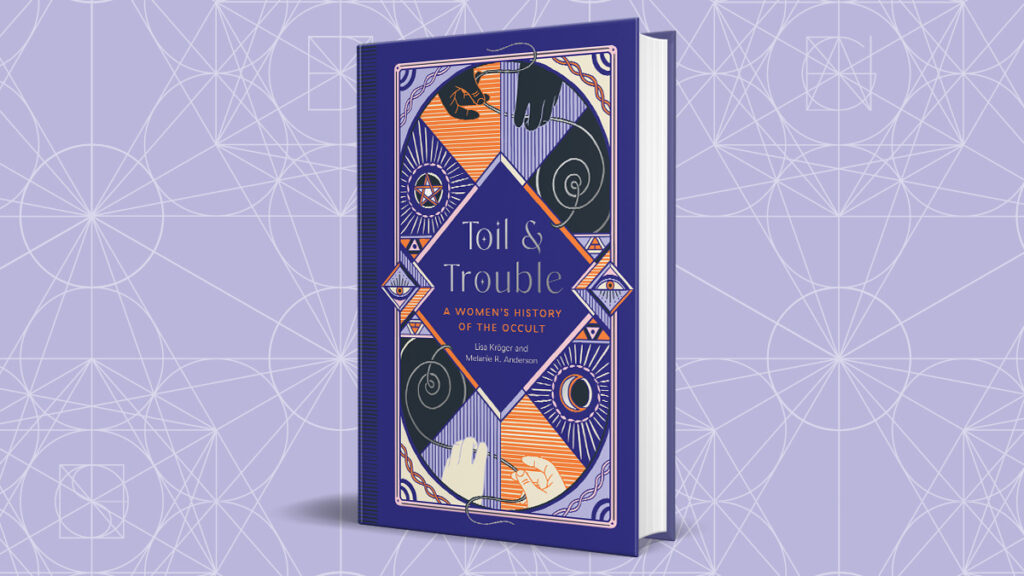

So how did this shift happen? When, precisely, did our cultural attitudes swing towards acceptance? These were the driving questions behind our research for our newest book, Toil and Trouble: A Women’s History of the Occult.

The earliest spark for what would become this book began in a surprising place with Twitter, Donald Trump, and singer Lana Del Rey.

We previously wrote a book about women and horror, so we’ve always had an interest in the occult (the occult was referenced in our previous book Monster, She Wrote). However, starting around 2016, we saw something new that sparked the conversations that would eventually form Toil and Trouble: modern day witches, including Lana Del Rey, taking to online forums and sharing dates and ingredients for occult rituals to bind recently elected President Trump’s powers. The dates? They corresponded with the waning crescent moon, a time symbolic of shedding negative energy and getting rid of stress in your life.

Here were a group of people—a lot of them women, transwomen, and members of the nonbinary and queer community—actively participating in rebellion against an oppressive power. It was a moment of occult protest.

Quite honestly, we couldn’t wait to jump into this research.

With the Trump administration and the accompanying moral panic of the QAnon movement, it seemed natural for our research to include the Satanic Panic that swept the United States in the ’80s and early ’90s. Between the Reagan administration, the Moral Majority, and the Satanic ritual sex-abuse hysteria surrounding daycares, the country was significantly more conservative than it had been in decades, and any whiff of occultism was feared, so much so that church women were clutching their pearls at the sight of toothpaste tubes (apparently the Procter and Gamble logo looked a bit too Satanic for some).

Yet, during this time, the Reagans themselves had an astrologer, Joan Quigley, in charge of scheduling dates for the President. It was hypocrisy, of course, but it also seemed to be an act of radical feminism. A woman might not have been President, but she sure could take charge of one.

It’s a different kind of occult rebellion, but it was there. And it turned out she wasn’t the first. Past presidents (including Warren G. Harding) had access to occult advisors of some kind. These advisors offered spiritual and political advice, if not to the president, then to those close to him, often using the First Lady as a conduit. It was a trend that we saw unfolding over the course of the history of the United States: when women were denied seats at tables of power (usually due to some sort of patriarchal or religious conservatism), they found an alternative way to make their voice heard. And that usually was through some kind of occult means.

That thread formed the basis for our new book. Any time women were limited by the patriarchy, the occult had a way of slipping into their methods of resistance.

In the 19th century, with the development of Spiritualism, women who were socially relegated to domestic roles used the occult to turn this situation to their advantage. If women were denied economic power outside of their homes, they could use their work as mediums communicating with the spirit world to attract paying customers to their parlors. If they were denied a political voice, they could communicate their views by being the ventriloquist for their spirit guides. Spiritualist mediums often transmitted messages from the dead that supported social reform movements of the time, such as the abolition of slavery and women’s suffrage.

Women were using the occult to redefine political power structures, but they were also using it to challenge, and sometimes even redesign, Christianity, which has always been closely connected to the patriarchy.

For example, in the 18th century, Jemima Wilkinson began a new version of Protestantism, the Society of Universal Friends, that was more open to women’s membership and leadership roles. Wilkinson became known as the Public Universal Friend and tried to not use pronouns at all, in a bid to rise above traditional gender roles (followers would later use he/him to refer to the Friend). Following in this path, in later centuries, various second-wave feminists would try to decenter the patriarchy from religion to include “goddess” language.

One thing we learned (that is really unsurprising) is that the history of the United States is one that is often told from a position of white, male privilege. By looking through an occult lens, however, we’ve learned that there was another side to this story. The U.S. has a pattern of women (and nonbinary people) participating in the occult and using it, when they could, to find ways to create opportunities, space within oppressive systems, and supportive communities. They are the people who are working to make sure that other voices are heard.

As we discovered in writing Toil and Trouble, the arc of the occult is bending towards inclusivity, and that is something to be celebrated.

A Book You May Enjoy

Lisa Kröger and Melanie R. Anderson

Lisa Kröger holds a PhD in English. Her stort fiction has appeared in Cemetery Dance magazine and Lost Highways: Dark Fictions from the Road (Crystal Lake Publishing, 2018).Melanie R. Anderson is an assistant professor of English at Delta State University in Cleveland, MS. Her book Spectrality in the Novels of Toni Morrison (Tennesee Press, 2013) was a winner of the 2014 South Central MLA Book Prize.